This Monday morning I said goodbye to the Colonel. A part of him anyway. Sunday night at Los Angeles’ Mark Taper Forum, we played the final performance of Father Comes Home From the Wars.

Now, if and when it becomes necessary to play a bearded character, an actor must relinquish control of his face to the play. There was no mention of a beard in Suzan-Lori Parks’ script, but in my mind, I hung one on the Colonel right away. He seemed to like it.

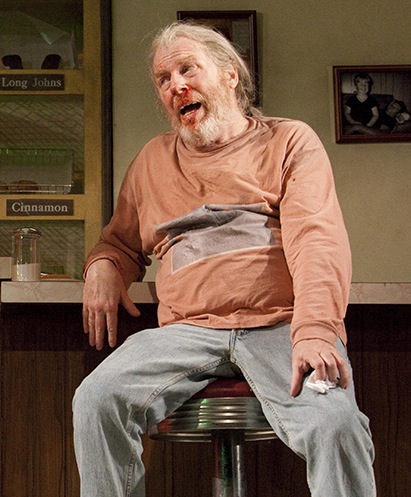

By the end of the run, the facial situation had gone rogue: a big white whiskerbush, a quarter-pounder. Thus, Depilatory Monday, a ritual razing of the tonsorial particulars of one’s character, in aid of looking like oneself again. I’m not a person who grows beards for sport.

The Broadway run of Tracy Letts’ Superior Donuts ended on January 3, 2010. The company’s Secret Santa scheme landed me an all-expenses paid shave and haircut at the legendary Paul Molé barber shop. Cliff Chamberlain, a moronic hood in the play and a perfectly nice smart guy in real life, had casually asked if I were keeping the beard past the play’s closing date. I answered in the negative, and Cliff made a reservation in my name. A very nice Christmas present.

Molé’s is a fine specimen of Old New York, then playing out its 99-year lease before moving across Lexington to their new squat. I sat in John Steinbeck’s chair of choice and let the barber barb. I’d never been shaved by a pro before, so the Missus took pictures to commemorate the occasion. I emerged from the fuzzy facial cocoon of chicago donut monger, Arthur Przybyszewski, ready for the next, hopefully clean-shaven, character.

Nope.

I personally got rid of the beard I’d grown for Gloucester in The Public’s 2011 King Lear. That play, by up-and-comer William Something, actually made reference to my guy’s chin spinach: Lear’s second-worst daughter, Regan, plucks Gloucester’s beard as foreplay to removing his eyes. Regan was played by our Kelli O’Hara. I know, right? Sweet, decent Kelli! Heartless!

Anyway, no more show, beard must go. Depilatory Monday, 2011-style.

May 16, 2016, it was the Colonel’s turn. I had decided to once again put it in the hands of the pros, in this case The Barbershop Club at the LA Farmer’s Market. Decent jazz on the speakers, comfy chairs, the able Marshall rocking the razor. Not as authentically old-school as Chez Molé, but a homey, unhurried atmosphere, nicely redolent with bay rum. The Missus watched the proceedings; no pix this time, just eager anticipation of good ol’ pink Mikey’s reappearance.

“There he is”, Nette said.

I’ve buried the lede deeply enough. Father Comes Home From the Wars was an exceptionally rewarding experience. The vastly talented cast (many from the Public’s New York production and, earlier, the Cambridge run at American Repertory Theater), the brilliant director Jo Bonney, the production staff and crew, all conspired to make this gig a great one. The Colonel himself was about the worst human being I’ve ever played: proud defender of the Confederacy and Southern rights, a “drunken dumb Jeb”, as another character calls him. He eloquently (or unstoppably, anyway) expresses views one might term repellent, very repellent or extremely repellent. He is “grateful every day that God made me white” and makes a spirited case for his superiority. He’s such a shabby piece of crap, though. It’s clear he’s circling history’s drain, making one last desperate stab at the respectability he’s imagined for himself. Audiences are not disappointed to learn of his timely death.

I loved the Colonel as I must love every character I work on, without judgment. If my assumption of the legitimacy of his beliefs serves the play, then that’s the job. I grew a beard and built a scabrous, sadistic bully to go behind it: a whorin’, slave-ownin’ drunkard who thinks very highly of himself and his glorious Confederate cause.

Close the show, beard must go. The Colonel is dead. His whiskers belong to the ages. His uniform is on its way back to the shop. I’ve had a wonderful time working with this incredible bunch and playing this beautiful play and I’ll miss it. But I will not miss the Colonel, exactly. He’s not my type. And he’s no longer my problem. Amen.

Depilatory Monday is all about “amen”.

Photo credits: Craig Schwartz (Father Comes Home…); Robert J. Saferstein (Superior Donuts); Public Theater (King Lear)

Shared with a friend who’s currently rehearsing Claudius in a play by William Something. Claude is just as much in need of a shave and no judgment as the Colonel is, so this should be just the thing. Thanks!

LikeLike

At the risk of spiralling into an infinite regression of subjective clarification, would it be more precise to say “It’s clear he’s circling history (as depicted in this play) ‘s drain, making one last desperate stab at the respectability he’s imagined for himself” and “…[He] thinks very highly of himself and his glorious Confederate cause (as depicted in this play).” ? Off, off Broadway, slavery was on it’s way out after the industrial revolution, and the legacy of Lincoln’s war has been one of more division and bloodshed than a few more years of slavery ever would have accomplished. That’s not Father Comes Home From the Wars or Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but 150+ years of objective historical perspective. Many in the south simply wanted a chance to gradually transition into industrialization in peace without threat of force from the opposing political party in the north who financially benefited from slavery as well. In a worldview where Lincoln wears a good-guy badge and a Superman cape there is no place for the above arguement. Can Father Comes Home From the Wars prepare an actor for the Confederate experience any more than King Lear can prepare one for the blind experience? Spinal Tap certainly could prepare one for the rock experience because they actually rocked, but are not the preceding examples a bit like pronouncing “I’m not a Confederate, but I played one on the stage”?

LikeLike